A tale of cowardice, colonialism, and blind faith, it’s hard to really know where to start with Grand Tour, a whistle-stop tour of Southeast Asia across the last century from Portuguese auteur Miguel Gomes. Part 1917-set romantic farce, part modern travelogue, it’s an often fascinating yet just as often irritating experiment with a lot on its mind but too little really in its heart, ultimately more of an intriguing curio than something that will truly punch through and stick with you.

We start in present-day Myanmar, in full colour, watching a traditional puppet show in the first of many modern documentary interludes that Gomes provides us with, before a Burmese narrator introduces us to the story of Edward (Goncalo Waddington) and Molly (Crista Alfaiate). These are the ‘heroes’ we’ll follow in the black-and-white 1917 segments, hopping across multiple countries in Southeast and East Asia, their story told both through their actions and through the voiceover narrators (framing the whole thing as if it were being read from a storybook), always speaking the native language of wherever these two find themselves.

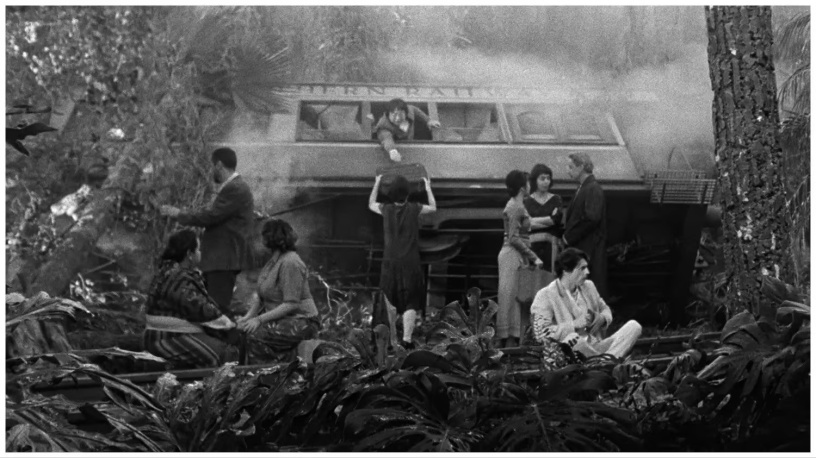

Edward and Molly, though, do *not* speak their native tongue – in a sort of inverse of Shogun from last year, here we have Portuguese being spoken as if it were English. See, despite being played by Portuguese actors, Edward and Molly are Brits, him a low-level Imperial official stationed in colonial Rangoon, her his feisty fiancée who, after a seven year engagement, has finally followed him out to Asia to actually get married. In a cold-feet panic, though, Edward flees for Singapore just before Molly arrives in Rangoon, and from there will keep on running to Siam, the Philippines, French colonial Vietnam, Japan, and China, getting roped into little vignettes with both old British acquaintances and locals along the way.

Molly, far more spirited than her groom-to-be, gives chase, always just a few steps behind. Given its jungle navigating, bandit dodging, and geopolitical stakes, Grand Tour is surprisingly gentle, always unhurried and with wryness being the overarching tone both in the doomed romance and in Gomes’s commentary on colonialism. Most of the best writing comes from his ability to have the imperial mindset be a part of Edward and Molly that comes to them as naturally as breathing, its omnipresence allowing Gomes to actually *avoid* didacticism – there’s no need to beat the audience over the head with a message they can simply drink in from the surroundings.

And they are immersive surroundings, gorgeously shot by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, always halfway between reality and artifice. Within all this cleverness and prettiness, though, it’s very hard to actually connect with Grand Tour. Some of the documentary footage is exquisite, like a scene in which a Filipino man brings himself to tears with his own profoundly soulful rendition of Sinatra’s ‘My Way’, but it’s also always interruptive and often just sort of perfunctory; it’s not particularly novel or revelatory to see how Japan is different now than it was a century ago.

Ultimately, Grand Tour actually shares its biggest flaws with its own protagonist. It’s too fussy, too evasive to make an emotional impact, a shaggy dog story with a beautiful and fresh setting. Maybe in an actual cinema it would be captivating, but most people (including me) will never know – it’s been sent straight to streaming without even a sniff of a theatrical run, which doesn’t allow it to put its best self forward. This is hardly the film’s own fault, of course, but, as a laptop watch, I can’t imagine many people sitting all the way through Grand Tour without at least a couple checks of the time.