Every new Wes Anderson film is always met with a similar response, meant as praise in one quarter and criticism in another; ‘he always makes the same movie’. On the surface, it’s a bit true (and why I mostly love his work – if no one else is going to make films like this, why stop the one guy who does?) but, to chop up an old truism, the more things stay the same, the more they change. Though it too features a star-studded ensemble cast, inch-perfect framing, and intricate-yet-kitschy sets, The Phoenician Scheme is Anderson’s biggest left turn since Fantastic Mr Fox, a far bleaker and more spartan effort than any of its predecessors in the last 15-or-so years, a tactic that is both fascinating and, ultimately, sadly cold and alienating.

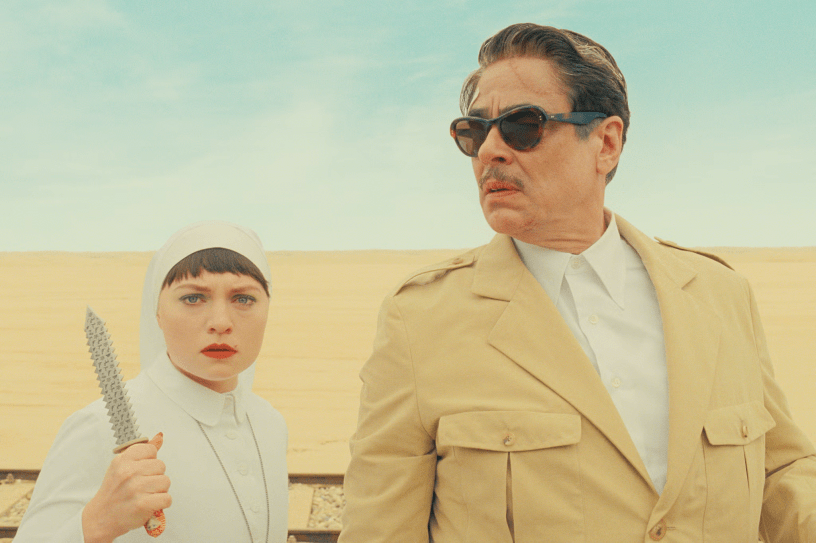

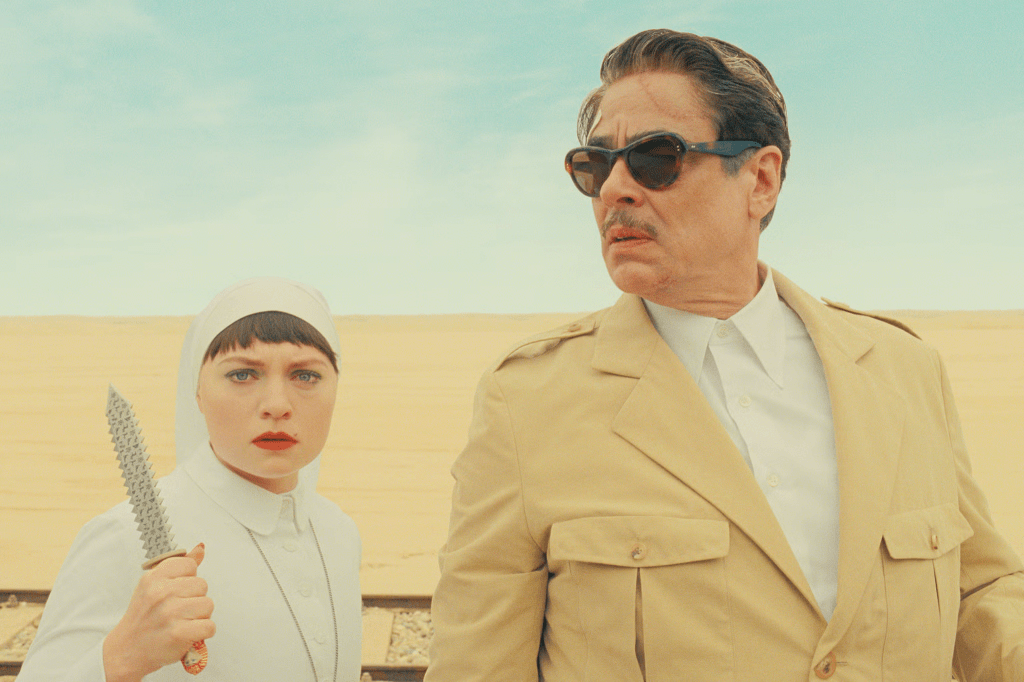

The most basic shift here, despite a cast list that runs at a typical Andersonian length and star-wattage, is that The Phoenician Scheme is far, far less ensemble-y than The French Dispatch or Asteroid City. Instead, just three characters take constant centre stage – industrialist and war profiteer Zsa Zsa Korda (Benico del Toro), his estranged nun daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton, aka Kate Winslet Jr), and gentle-natured Norwegian entomology professor/administrative clerk Bjorn (Michael Cera).

Korda needs Liesl and Bjorn’s help to finish his life’s work – a series of massively ambitious construction projects in a fictionalised 1950s Levantine super-state for which he has run out of cash and now must navigate tricksy diplomacy and constant assassination attempts to finish. It’s unclear how much stake Anderson actually has in this plot and it is pretty hard to care about, no matter how many fun names for everything Anderson comes up with, the political intrigue clashing with the cartoon logic that Anderson stories generally run on. The real focus is on the father-daughter stuff between Zsa Zsa and Liesl, and this is better, though still more icy and distant than the best heartfelt stuff from, say, The Grand Budapest Hotel or Moonrise Kingdom – Zsa Zsa is Anderson’s most morally dubious ‘hero’ yet, and sincerity does not come naturally to him.

Del Toro and Threapleton each give compelling performances, though are naturally outshone by Cera, who is a new addition to the Anderson ensemble but fits in like he’s been there for 20 years, a perfect match of actor and material. Elsewhere, Jeffrey Wright is *again* an MVP within just one scene, while Riz Ahmed, Richard Ayoade and Benedict Cumberbatch all graduate from Anderson’s Dahl shorts to full big-screen players very well. It has to be said that The Phoenician Scheme is maybe the least outright funny Anderson film ever, always leaning more *wry* than laugh-out-loud, but he has staffed his cast with masters of this discipline (while the sillier long-term players like Jason Schwartzman, Adrien Brody, and Edward Norton are absent).

It almost feels redundant at this point to talk about Anderson’s visuals, but they are again perfect. Bleaker and less absurdly complex than, say, The French Dispatch, his controlled camerawork, distinct colour schemes, and heightened and mobile sets still delight here, from rickety old aeroplanes to gorgeous architectural models. It is also remarkable how much *quieter* The Phoenician Scheme is than its predecessors, far more scenes playing out with exclusively diegetic sound than we’re used to from Anderson.

The end result is something more tense and choked than you’d expect, either from recent Anderson efforts or this film’s own marketing. It’s an admirable and intriguing shift in focus and tone from a filmmaker who could perhaps be called predictable, but the recent Wes oeuvre hasn’t been fantastic just because of perfect design and big quirky laughs – it’s also down to an earnest big-heartedness that grounds everything in a genuinely affecting way. The Phoenician Scheme hasn’t quite brought enough of that along with it.