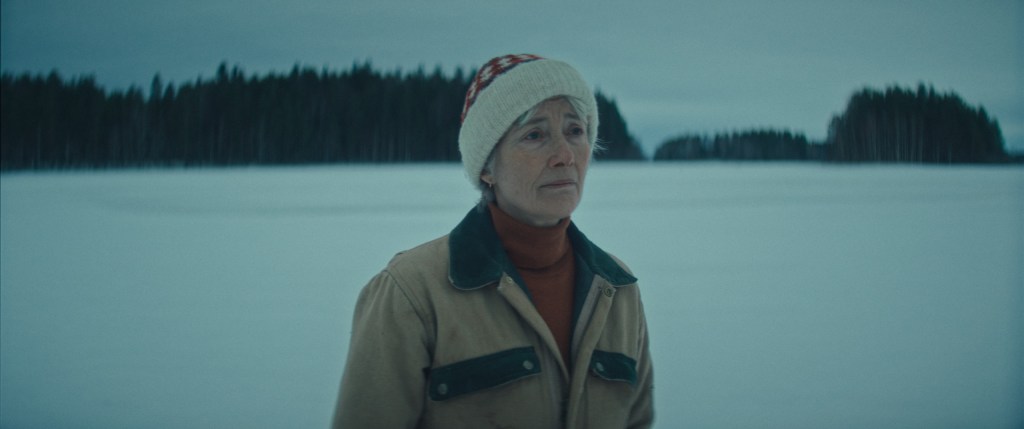

As far as elevator pitches go, Brian Kirk’s Dead of Winter doesn’t have a bad one; ‘what if Fargo, but with Emma Thompson?’ It’s an immediately attention-catching idea, though somewhat dampened by the fact that it’s also ‘what if Fargo, but without any Coens?’ The result is an enjoyable enough snowbound rural Minnesota thriller with a great use of the endless sky and grey-glinting ice but a weak ensemble of characters, none of whom entirely convince even though there’s only really four of them to work with.

Thompson plays Barb (though, like most of the cast, she spends most of the film unnamed), a tough old bird of a lifelong Minnesota woman (her accent is decent, but far from the perfection achieved by Frances McDormand or Martin Freeman in the actual Fargos). Heading out on a trip to do some ice fishing and scatter her late husband’s ashes on the remote, isolated frozen lake on which they first fell in love, she gets a bit lost, stumbling upon a cabin in the nearby woods in which a mysteriously sinister couple are holding a young woman they’ve kidnapped in what looks like a scheme to steal her organs. Outnumbered and outgunned, Barb nevertheless steels herself to do the right thing and save this girl.

And, some flashbacks to Barb’s younger years (in which she’s played by Thompson’s actual daughter Gaia Wise), aside, that’s all there is to Dead of Winter. The whole story takes place over less than 24 hours, with Nicholas Jacobson-Larson and Dalton Leeb’s script sparse on dialogue. This does work for Barb, whose mix of gutsiness and sheer decency is a good fit, if not exactly a stretch of skill, for Thompson, but leaves the villains of the piece feeling underdeveloped and unconvincing.

These are a manic and vicious wife (played by Judy Greer) and her physically imposing but ultimately snivelling husband (played by Marc Menchaca). As a duo, they make for effectively nasty obstacles for Barb to overcome, but it’s hard to buy in to both their plan and then how rabidly they commit to it even as Barb throws multiple spanners in the works. Fittingly for the bleak and empty milieu, Dead of Winter is pretty muted (even making too little use of Volker Bertelmann’s punchy score), which makes it admirably lean but also weakens the thrills when the people involved don’t feel like, well, people.

The setting does pick up a lot of the slack, though, even if the sheer sensation of cold isn’t as bitingly omnipresent as you feel it should be, shot unfussily but effectively by DP Christopher Ross. Vast nothing stretches out infinitely once the action actually gets to the frozen lake, really selling the despair of the story in a way that the words themselves rather fail to do, while the strange, alien rumblings of thick ice expanses make great punctuation for certain scenes. As the nights draw in for Autumn, Dead of Winter may, counterintuitively, be a sort of comfort viewing – the kind of unchallenging but inoffensive mid-level film that you can watch in a snug room with a warm drink and think ‘at least I’m not that cold’.