Though it is an absolutely done-to-death genre, there’s always room in my heart for a big old World War 2 drama, and James Vanderbilt’s Nuremberg is here to be 2025’s entry into that canon, telling the story of the trial of Hermann Goering and the Nazi high command. It might not hit with the incredible character work and bombast of Oppenheimer, the formal boldness of The Zone of Interest, or even the tonally confused pluck of Blitz, but it still ends up an eminently watchable piece with a very entertaining central performance from Russell Crowe as Goering.

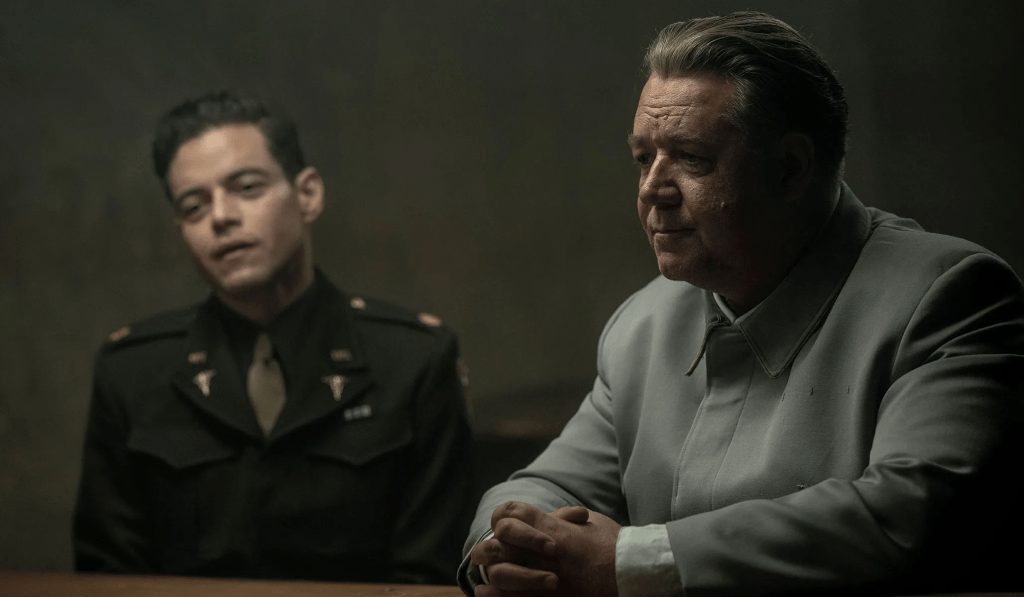

Sized up to blimpish proportions, Crowe makes expert use of his heft, Goering’s weight intimidating instead of funny, able to envelope the frame, engulf a room. It’s backed up by a commanding, narcissistic confidence that can even be grimly charming, whether Goering’s sitting in his cell with the American psychiatrist assigned to evaluate his mental stability or sparring with the prosecutors in the trial itself. This psychiatrist is Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek, in a role that would have actually fit Crowe down to the ground if this had been made 25 years ago), whose primary goal was to keep his Nazi ‘patients’ from killing themselves but found himself getting inexorably wrapped up in his fascination with their evil.

Malek, who serves as Nuremberg’s actual lead even if Goering naturally dominates the conversation, and Crowe make for a very solid leading duo, with able support from Michael Shannon as the American prosecutor in the actual trial, even when Vanderbilt’s script wobbles, which happens pretty frequently. Nuremberg zips along at an impressive pace even while running at two-and-a-half hours, but a lot of the writing here is, to put it plainly, pretty dumb. Odd beats that rely on characters suddenly being dumbed down for a moment are too common, and the exposition is poor, often treating the audience as if this is their first exposure to World War 2 and the Holocaust.

If all this has sounded a little too upbeat and easygoing for a film dealing with the abominable crimes of Nazi Germany and the subsequent trial (possibly the most important and influential in human history), that’s because Nuremberg is surprisingly light-hearted at first. Kelley and Goering get on, to the point that Kelley even befriends the Nazi Reichmarshall’s wife and daughter, and it’s one of Vanderbilt’s most effective conceits in how this flips. As the characters finally learn of the true horrors of the camps, so too does the film do away with any pretence of chumminess, the morally grey quagmire Kelley has found himself in reverting sharply back to black and white.

Talking of grey, black, and white… Nuremberg is not a very good-looking film. Washed out colours and constant darkness even in daylight make sense for an oppressive atmosphere, but the effect is more dull than immersive. It’s particularly galling when Vanderbilt goes into one of his very sparingly used flashback sequences, which pop with eerily gaudy colour, a far more interesting and imaginative stylistic tic that I wished the film had the confidence to stick with.

As all the most middle of the road World War 2 films are, Nuremberg is pretty much custom built to fill a Sunday afternoon on the telly, where the uninteresting visual work and inconsistent writing quality take a back seat to it just being a really solid combo of weightily important subject matter and great pacing. It’s a proud tradition to sit in, one whose practitioners I always have a soft spot for, telling a familiar story with gravitas and a recognisable cast. Sometimes that really is all you need.