If you were to be inspired to read the source material after watching the lovely new French animation Little Amelie, what exactly that book would be called will be drastically different depending on where you are. For English-language translations of Amelie Nothomb’s semi-autobiographical short novel, you’ll be looking for The Character of Rain, but in the original French, it’s The Metaphysics of Tubes. Combined, these two titles present a neat totality of Nothomb’s approach to recreating the life of an infant, halfway between the natural and pure quasi-divinity of rain and the endless consuming and excreting of a tube. Liane-Cho Han Jin Kuang and Mailys Vallade’s sweet and gorgeous adaptation, though, leans far more heavily into the rain, a magical study of early childhood and the beauty inherent in its wonder and imagination.

Amelie (Loise Charpentier) is a baby born to a Belgian family living in Japan in the 1960s for her father’s diplomatic work – wise well beyond her years, she also provides an omnipresent narration for the story. For the first 30 months of her life, Amelie is completely silent and still – not sickly or comatose, just entirely unmoved by the world – until an earthquake wakes her up. Her immediate response to sentience is, understandably, shock and fury, becoming a terror toddler until the interventions of her grandmother (Cathy Cerda), who teaches the wonder of life through the gift of white chocolate, and new housemaid Nishio-san (Victoria Grosbois), who shows Amelie the joys and fears of being conscious.

Crucially, both of these women share one trait – they treat Amelie like a person, not just a baby, Kuang and Vallade superbly capturing, through both their dialogue and visuals, the deep frustration of being very young, a stage in life where you have no agency and no one understands you, no matter how hard you try or how loud you shout. Nothomb’s original novel was heavily inspired by the Japanese notion of children under three being closer to gods than people, a concept Amelie herself understands innately, and it’s consistently funny to hear her confidently opine on her own brilliance.

Almost every moment of Little Amelie is within this mode of gentleness; all the humour, drama, and adorable sweetness swimming around in softly moving harmony. It is a very slight piece, mostly necessitated by its tiny 78-minute runtime (of which a full 9 minutes is opening titles and closing credits, meaning the story itself barely scratches over an hour), but this mostly means it knows how to not outstay its welcome, even if a couple of moments are a little dramatically underpowered.

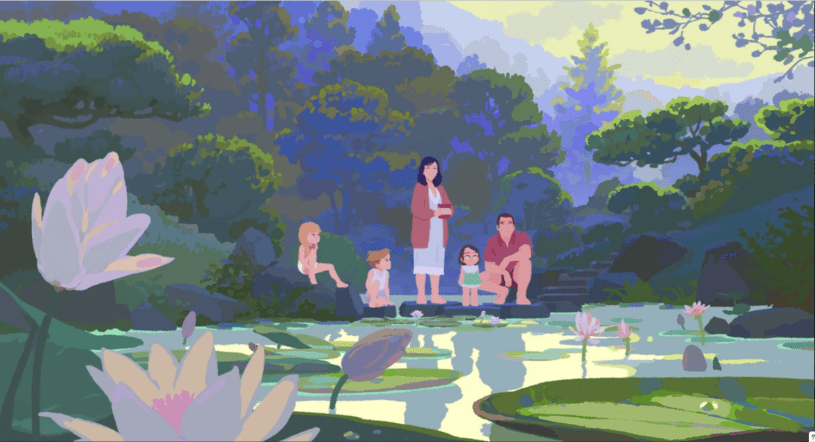

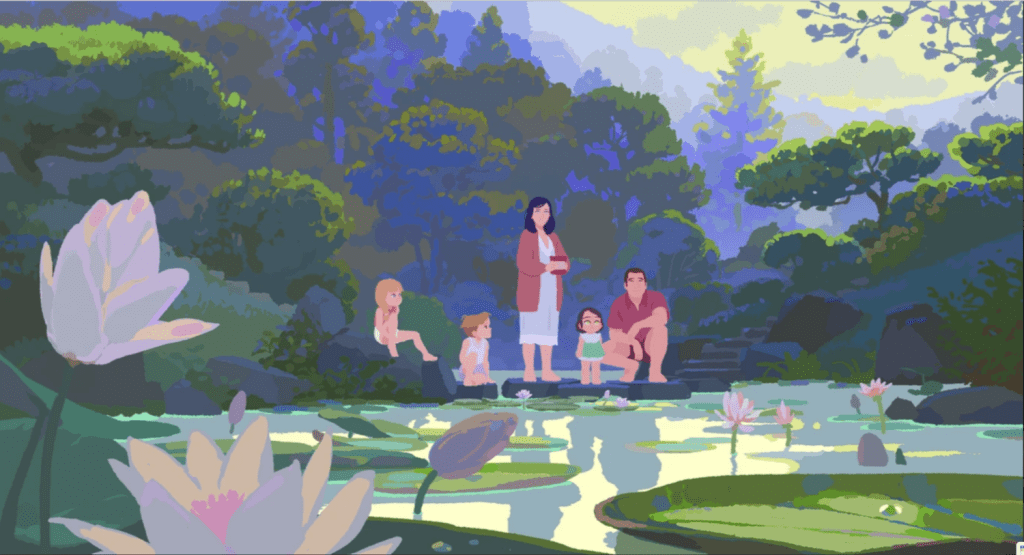

Everything is held together by the gorgeous animation style, blending an ethereal softness (very little here, whether for the characters or locations, has any sort of sharp edge) with a tactile everyday mundanity of a family home lived and loved in. Fitting for its story, Kuang and Vallade hit on an East-meets-West sensibility for Little Amelie’s style – the pair had previously worked as animators on Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist, and there’s a lot of that being melded with more anime stylings here. The result is a film as gentle visually as it is dramatically, a sweet and light way to expand any kid’s animated horizons beyond CG blockbusters and Disney bombast.